THE OVERFLOWING

The second of our commissioned responses to Woman in the Machine comes from Sue Rainsford, an art writer and author of two novels: Follow Me to Ground and Redder Days. In a recent talk, Rainsford spoke of not wanting to directly describe or ‘translate’ an artwork into writing, but rather responding interpretatively: to use language to dig deeper into the work and tease out threads, ideas and references which could be explored, or to bore into the emotional core of a work. In ‘THE OVERFLOWING’, her response to Woman in the Machine, Rainsford hones in on the works of four artists, using imagination, poetic language and literary references to untangle ideas of geofeminism, extraction, and its possible counterpoint, ‘ooze’. The text is available to read below or to download as a PDF.

THE OVERFLOWING

sue rainsford

E X T R A C T (v.)

to draw out, withdraw, pull out or remove from a fixed position

late 15c., from Latin extractus

The common definition of ‘extraction’ makes no allusion to the passing of time; it suggests a singular act of finite duration rather than a slow siphoning which can last a lifetime.

But ‘a lifetime’ is not a quantifiable unit of measurement when extraction has occurred. Depending on the body—which might be creaturely or terrestrial—‘a lifetime’ can signify minutes, decades, centuries, millennia.

Let’s say, instead, that extraction is ongoing.

Let’s say it shrinks and expands to glove itself around any resource of its choosing, and that this constant fluctuation makes it difficult to recognise.

A speculum between a woman’s legs, a drill gouged into the earth; what do they have in common? Insertion, but what else?

Insertion that edges into intrusion.

Intrusion with withdrawal as its goal; the cultivation of cells or earthly spoils.

The blades twist open: the red cavity is exposed. Light finds this dark interior.

Inside the earth’s crust the drill goes down and down: always, it can go a little deeper. Any moment, it will strike the planet’s molten core.

Until then, a woman is sitting at a loom and she is weaving. She knows that ‘the spindle and the wheel used in spinning yarn are the basis of all later axles, wheels, and rotations’.¹ She knows that ‘the interlaced threads of the loom compose very literally the software linings of all technology.’²

The earth rocks beneath her: for miles around all the coastal caves are rushing with foaming water. She looks to the window, but she needn’t look for long. She has seen storms before.

The lights go out, and still—her hands move across the loom.

TOUCH TECHNE

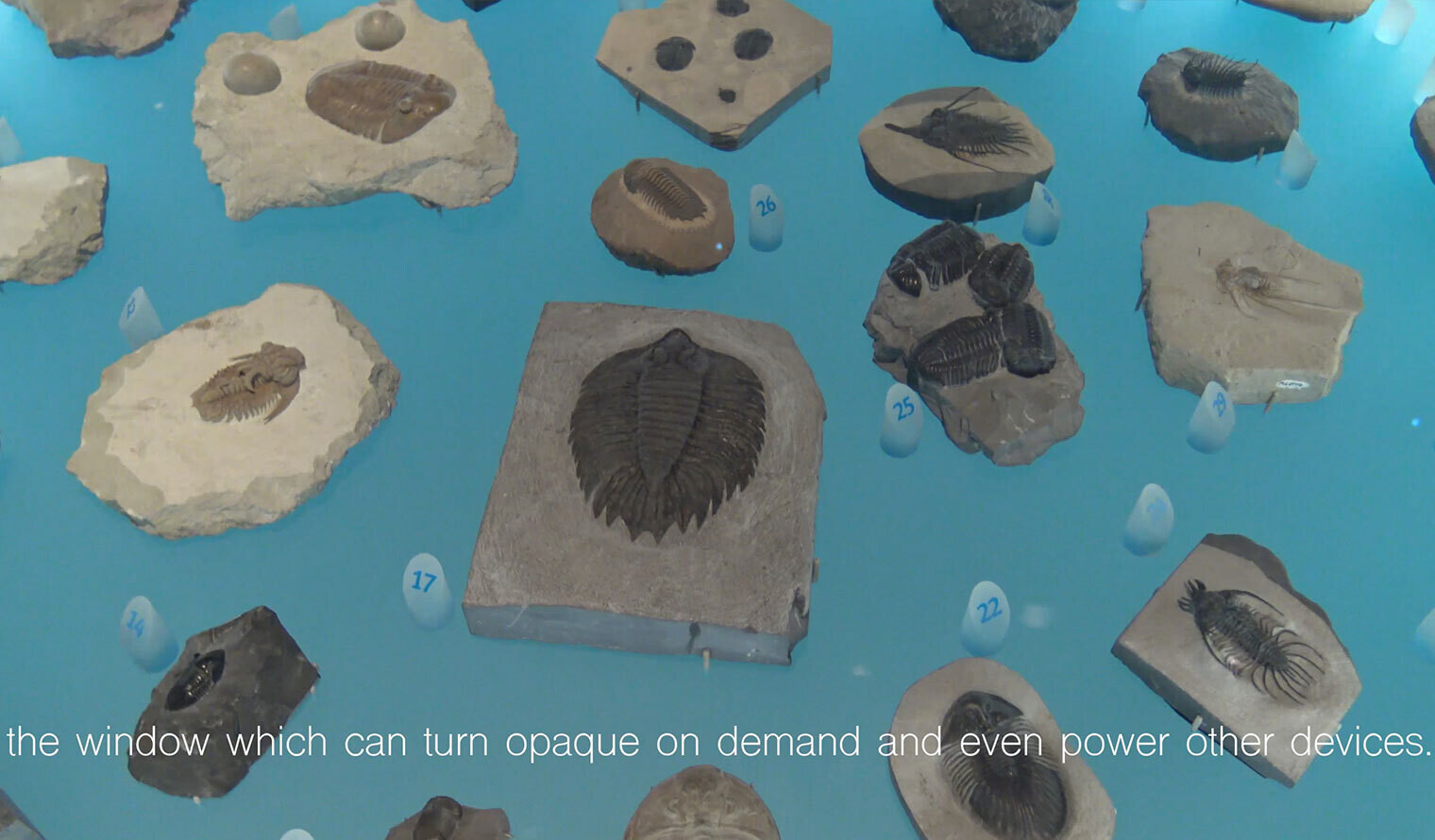

There are eight screens on the ground, which means you are looking down. Down there, at your feet, you see cross-sections of earth and sky and sea and leaf and skin and pelt. Their highly polished quality suggests a common archive. They are moving, these images, and now they are overlaid with ovals, ovals that contain images which are also moving. One holds a tiger’s eye widening and squinting. Another, a pocket of flame that retracts and combusts. Quickly, this gentle hypnosis takes over: the jellyfish undulating, the warm haunch of a furred animal in motion.

How many moments until you notice the indiscrepancies this trance holds at its core? When will you realise the sea creature overlays a leaf, the lush segment of fur the foaming surf? They don’t quite belong to one another, and you feel you could rearrange them with your eyes and your eyes alone if you had the time, the inclination.

But no matter what knowledge the brain accrues, the body—its eyes—is a place where we are easily seduced. Which is to say it is far simpler and far more sweet to stay still, and carry on looking.

Susan Howe poses the 19th century art collector Isabella Stewart Gardner ‘as a pioneer American installation artist.’³ Beneath Titian’s Rape of Europa in her namesake museum is ‘a long swatch of pale green silk’.⁴ A cutting from her wedding gown, paired with a portrayal of a woman who let herself be carried into the sea because she believed she was riding on the back of a bull rather than a shapeshifting, lustful god.

No One Can Embargo The Sun

In Teldavnet, Co Monaghan, a gold disc is retrieved from the ground: on one level it is an artefact and on another it is the sun. Or rather, it is what bronze age people saw when they looked at the sun: a flat circle in the daytime sky, brightly gleaming.

Can we say that sunlight lands all around us, indiscriminately permeating skin and soil, when this disc lives inside a vitrine?

Or when the 18th century saw Irish windows boarded up against the lateral entry of light?

Or when 21st-century solar technology sees it funnelled through careful apertures?

Decades will pass before sunlight ceases to intersect with silver deposits inside an arid mountain, with coin debasement and taxation. By that time, the law of ancient lights will be parsed in terms of opacity and optimisation, and sunlight will be entwined with another potent mineral withdrawn from the earth.

The fibers leading into the filaments of the first electric lights were developed by Edison and Swan. ‘When attempts to develop a more uniform light led to the use of nitrocellulose, “Swan prepared some particularly fine thread which his wife crocheted into lace mats and doilies that were exhibited in 1885 as artificial silk.”’⁵

Desmosome

Chthonic – part 1

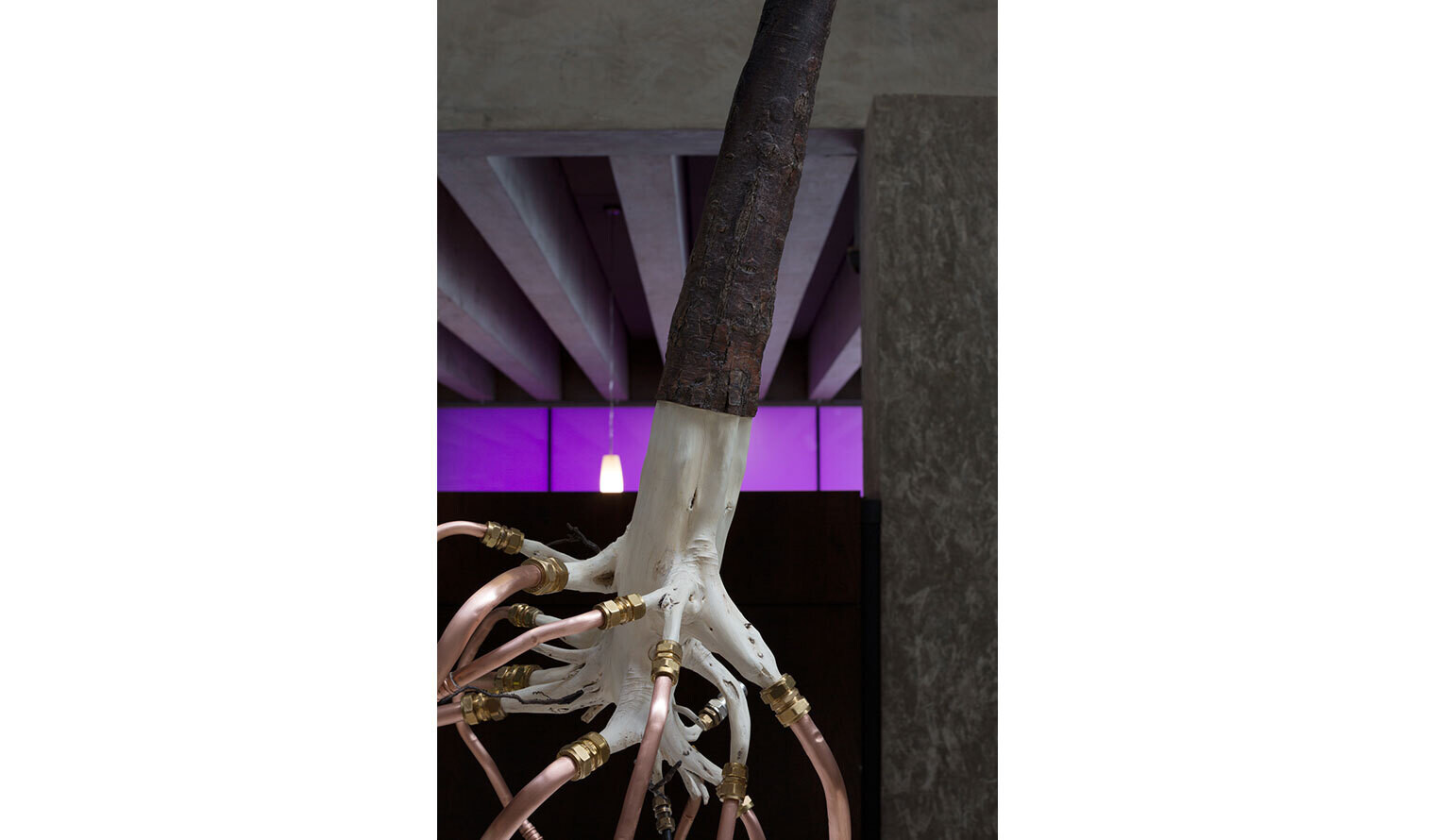

What you see, at first, are diverse textures exquisitely juxtaposed. Bolts affix tubes to branch-formations, tubes which are surely flush with nutritive fluid.

But no: it is the torturous inverse. A vital property is being sluiced off, rendering these pieces at once vegetal and industrial—medical.

For how many centuries can they survive like this steady, incremental petrifying? Already they are teetering, rearing back. They can’t quite catch their balance: at a cellular level they are in a state of frenzy—their every chemical compound is telling them to slink back underground and thread themselves through the rooty loam.

For as long as they are pinioned here, they are mutating. Like any other thing that is in any way alive.

Sarah Pierpoint Edwards: a mystic prone to bouts of spiritual ecstasy whose visions and writings were attributed to her preacher husband. In the archives Susan Howe finds a fragment of her wedding dress and reproduces it as a photocopy. More than her words scratched on paper, this is what survives: this miniscule piece of cloth, its fraying weave.

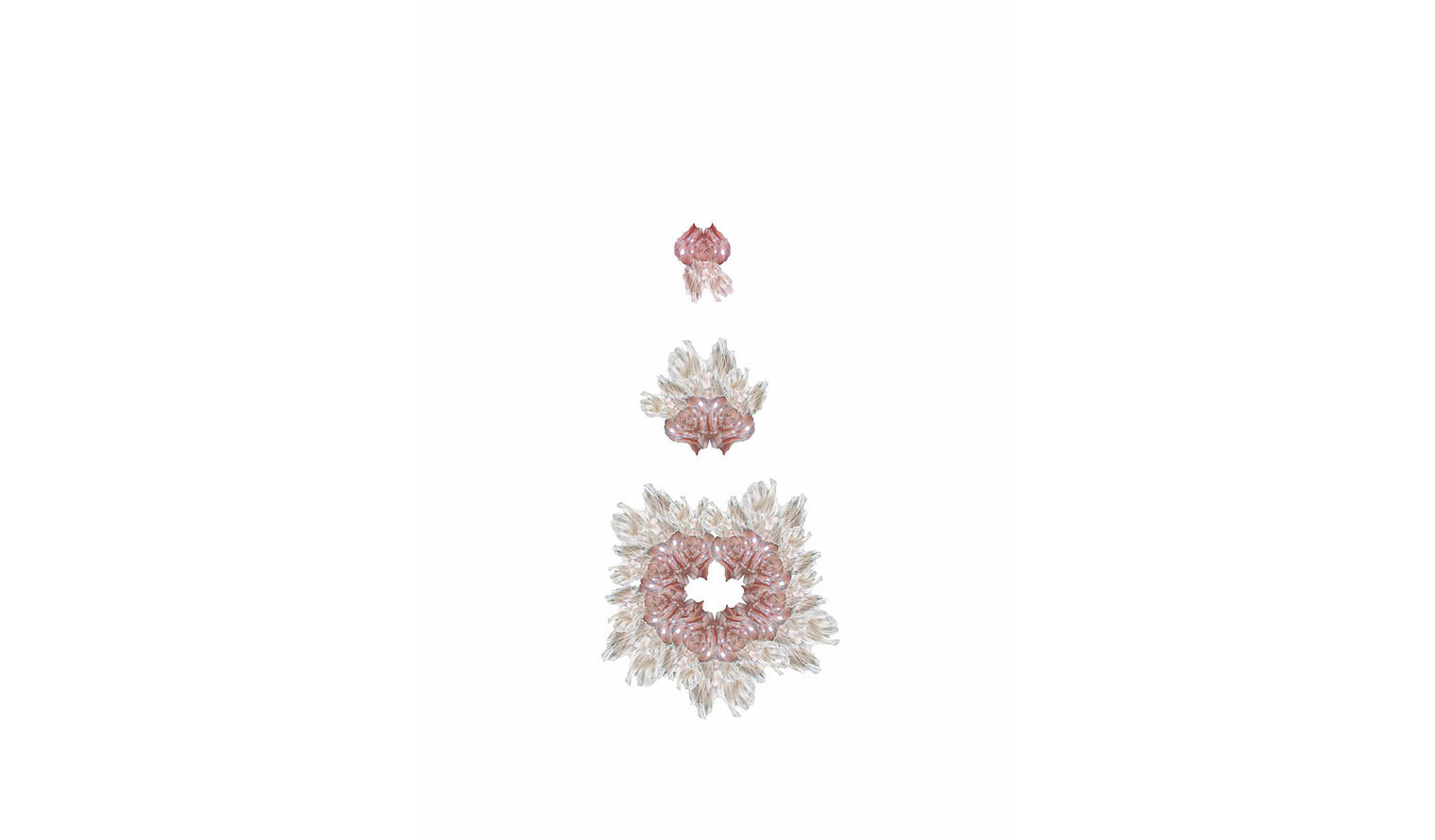

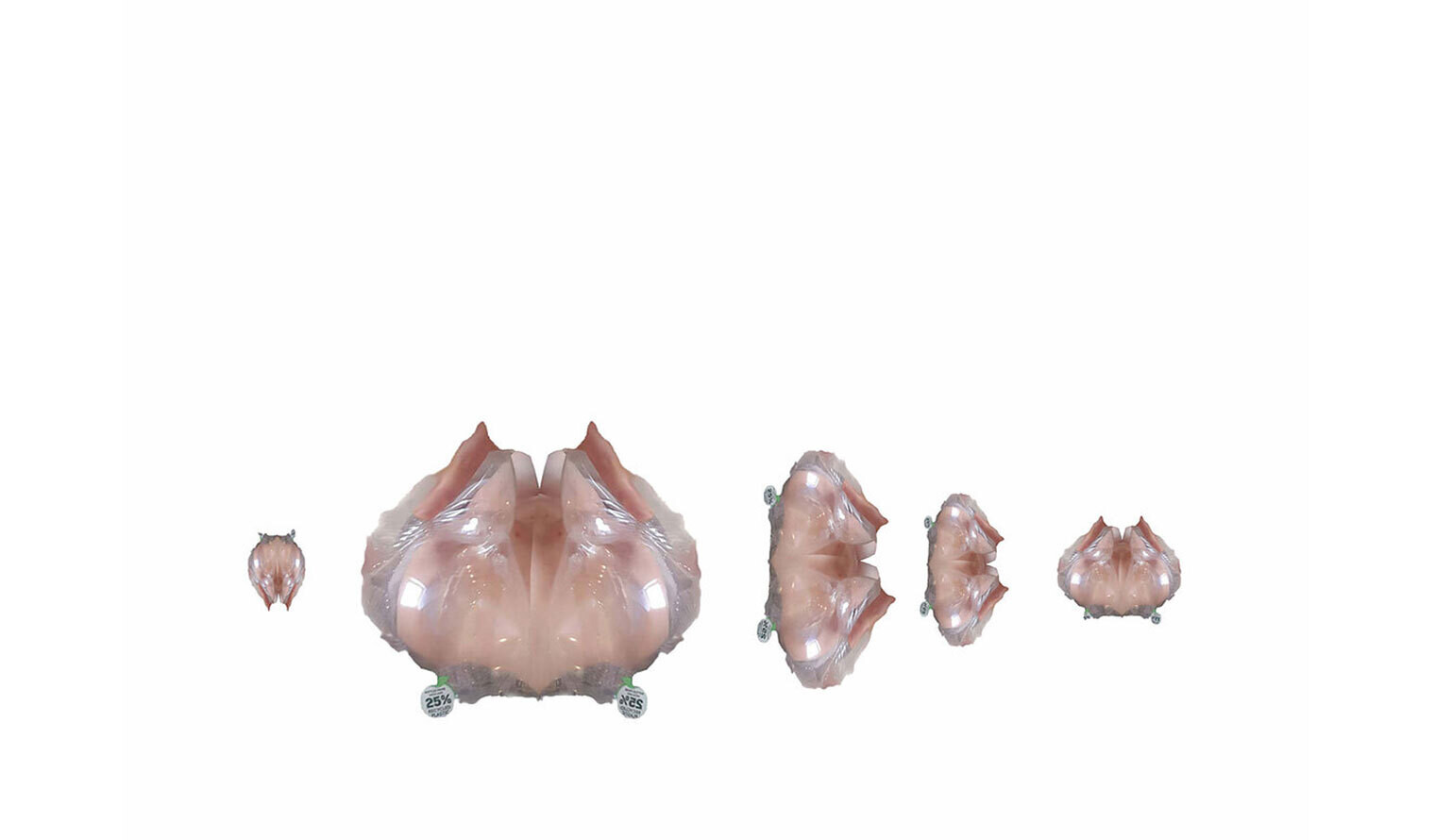

x humanoplaticus I

x humanoplaticus IV

In 5167 a vegetable nudges its way up through the soil. It is ripe, which is to say it has synthesized. It offers not only nutrition but enhanced lung capacity: if you eat enough of this vegetable you will be able to not only breathe but sing deep under water.

It is millennia from now, and every child born has a torso slightly more compressed than the one preceding it. Deep sea singing is the only way to survive this increasingly pressurized climate and so the waves are always loud with voices rising to catch acoustic currents.

No one who is currently alive has heard a song in a bar or a cathedral.

Nor do they think twice about eating the bounty of an earth whose soil is indebted to a hybrid species of mineral, whose grains are indebted to an ancient form of plastic.

O O Z E (v.)

(of a fluid) a perpetual ebb and flow

a process particular to feminine and soil-based bodies

Early 23c, from Eng. unfold

A woman is standing on top of a mountain.

But then ‘a woman’ is not a quantifiable measurement. A woman is immeasurable terrain. A woman might be a peninsula, a quarry, ‘the network of each nervous system relit with electric connections’⁶, or else a series of fleshy folds.

For now, we can say it is in the shape of a woman, this body, and that while she stands here she is saying ‘Look at me, I’m gushing, it doesn’t stop, but continues to drip...down to the underworld. For the longest time I

She stands here for a long time, so long that ‘...a membrane grows...it lengthens, it gives the women a sort of wing on either side of their body...two great flaps of silk.’⁸

From these openings in her body, she is secreting. The golden ooze marks the place her body remembers the world’s attempt to breach, to encroach.

Let us say that hers is a seeping body. Let’s say it is a body that slips the noose and runs bare legged into the copse. While she runs the trees are humming, the hills are rising. There is a movement, shattering and seismic, from somewhere deep below. She looks to the sky but she needn’t look for long; she has seen the sun before.

Now it turns away: hides its golden face.

It is dark, but no matter.

Her seeping body drops luminous wherever it touches the shaking ground.

Sue Rainsford

Footnotes

1 Plant, Sadie. Zeros and ones: Digital women and the new technoculture. Vol. 4. London, 1997.

2 Ibid.

3 Howe, Susan. Debths. New Directions Publishing, 2017.

4 Ibid.

5 Plant.

6 De Bingen, Hildegard & Lemmey, Huw. Unknown Language. Ignota, 2020.

7 Hval, Jenny. Girls Against God. Verso Fiction, 2020.

8 Wittig, Monique. Les guérillères. Minuit, 1969.