Interview with Fiona Mc Donald

Artist Fiona Mc Donald explains how she uses coding and electronics to represent nature in data-driven artworks

1 of 11

Fiona Mc Donald beside two of her artworks in Woman in the Machine

An artist whose work has always been at the nexus of art, science and technology, Fiona Mc Donald uses computing and coding to produce artworks that bring us closer to nature. Five artworks by Fiona are on display in the gallery at VISUAL as part of Woman in the Machine, and a sixth is currently available on womaninthemachine.com. All short video works, each one is generated using environmental data – from the Cooley Mountains, and from the gallery at VISUAL itself, where Fiona has placed a sensor to collect information in real-time for the duration of Woman in the Machine. Gathering data on light, heat and humidity, the sensor’s findings become the raw material for the artist’s sound and image works. We spoke to Fiona to find out more about her process, the importance of learning to code and the creative potential in data.

Can you tell us about traversing Cooley Mountains during lockdown – what was your experience of the mountain like and what were you there to do?

In 2020, I was awarded a residency in Technology and Innovation at Talent Garden, DCU Alpha. The residency began in the midst of the Covid pandemic: I was hiking in the mountains and reading The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd. Her writing reminded me of how on a mountain you become closer to and more aware of the mountain’s microclimate: small adjustments and fluctuations of temperature, humidity, light; the air we breathe and that touches our skin, as we navigate the terrain. The book describes how the mountain’s own atmosphere alters the light: “In a dry air, the hills shrink, they look far off and innocent; but in a moisture-laden air they charge forward, insistent and enormous, and in mist they have a nightmare quality. This is not only because I cannot see where I am going, but because the small portion of earth that I do see is isolated from its familiar surroundings, and I do not recognise it.”

During this time I was also working on a few new projects, leveraging different technologies. I had been working with a company called Taoglas, a leading enabler of digital transformation through the Internet of Things (IoT). I was lucky enough to get my hands on one of the company’s Taoglas EDGE™ IoT starter kits. I started bringing the kit up into the Cooley Mountains and used it to track my position and collect weather data, ambient light, temperature and humidity. The kit monitors and collects data and sends it back to Taoglas Insights, a cloud-based software platform, in real-time. Typically found in E-Scooters, I was interested in how I might apply these technologies with new agendas in unexpected ways on the mountainscape, collecting different data sources to create something quite different and poetic.

As Nan Shepherd describes in her book, “The thing to be known grows with the knowing”. Although I had gazed on and visited the mountains many times over the years, I was excited to discover some locations I had not been aware of before – a lake on a mountain top and a blanket bog.

Has experimenting with technology always been part of your practice? When did you learn to code?

I have a background in Chemistry & Fine Art. My practice was always situated at the intersection of both disciplines and often included experimenting with analogue devices and voltage to create generative works. An MSc in Multimedia Systems gave me experience in hardware and software; Processing, a visually-oriented Java-based programming language created for artists and designers; sensor technology and Pure Data, a visual programming language for creating interactive computer music.

Since then I have worked in the area of physical computing, using live data feeds from local sensors or networks (such as satellite data from the Gamma-ray Coordinate Network, or GCN) to create generative works that aim to make scientific data more visible. I think in this field you never stop learning, you are always building on your knowledge through online courses or collaborative projects. Recently, I’ve worked with python code and P5.js, a Javascript-based coding language that allows you to create web-based interactive works.

Can interpreting data be a creative process?

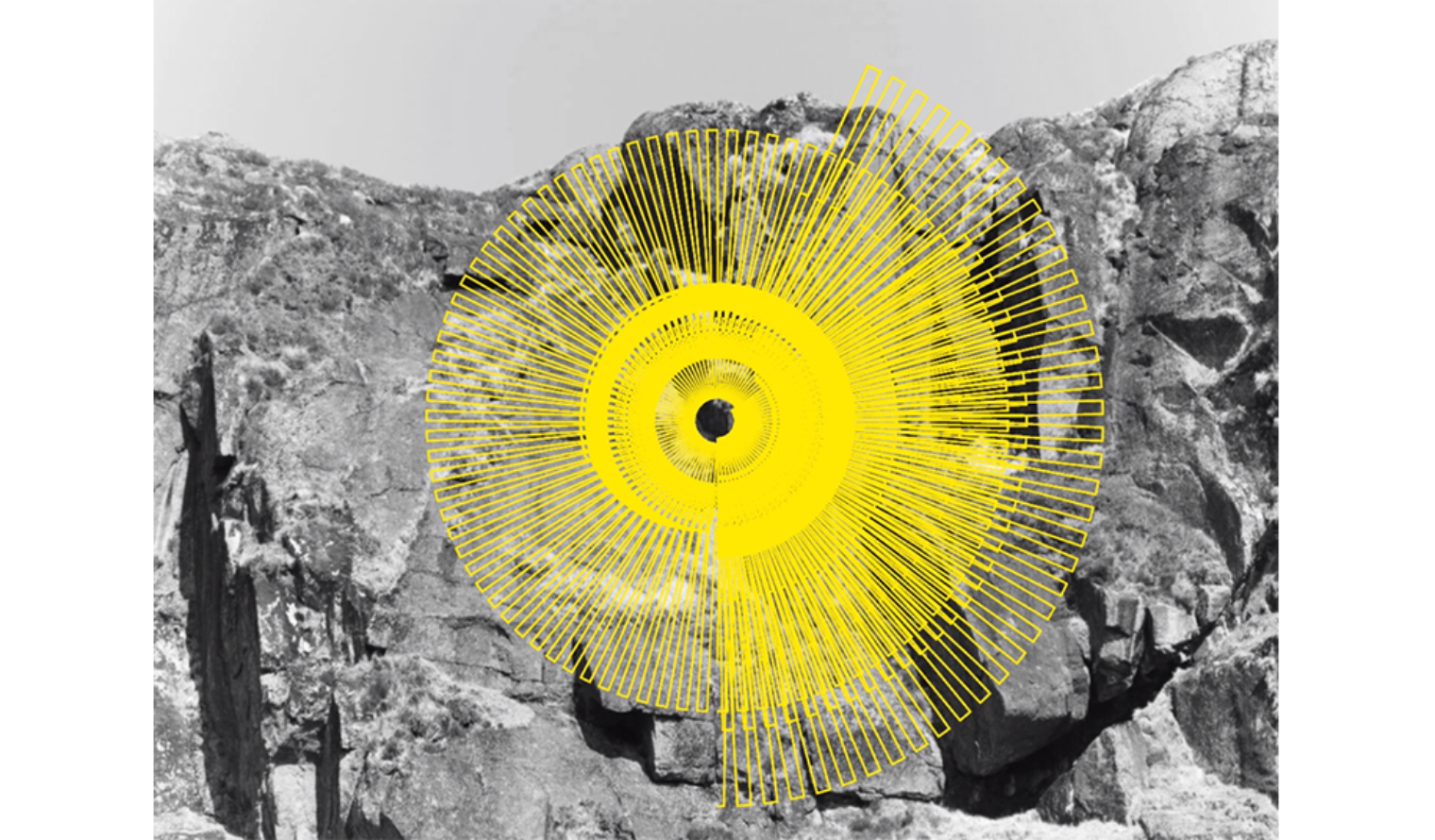

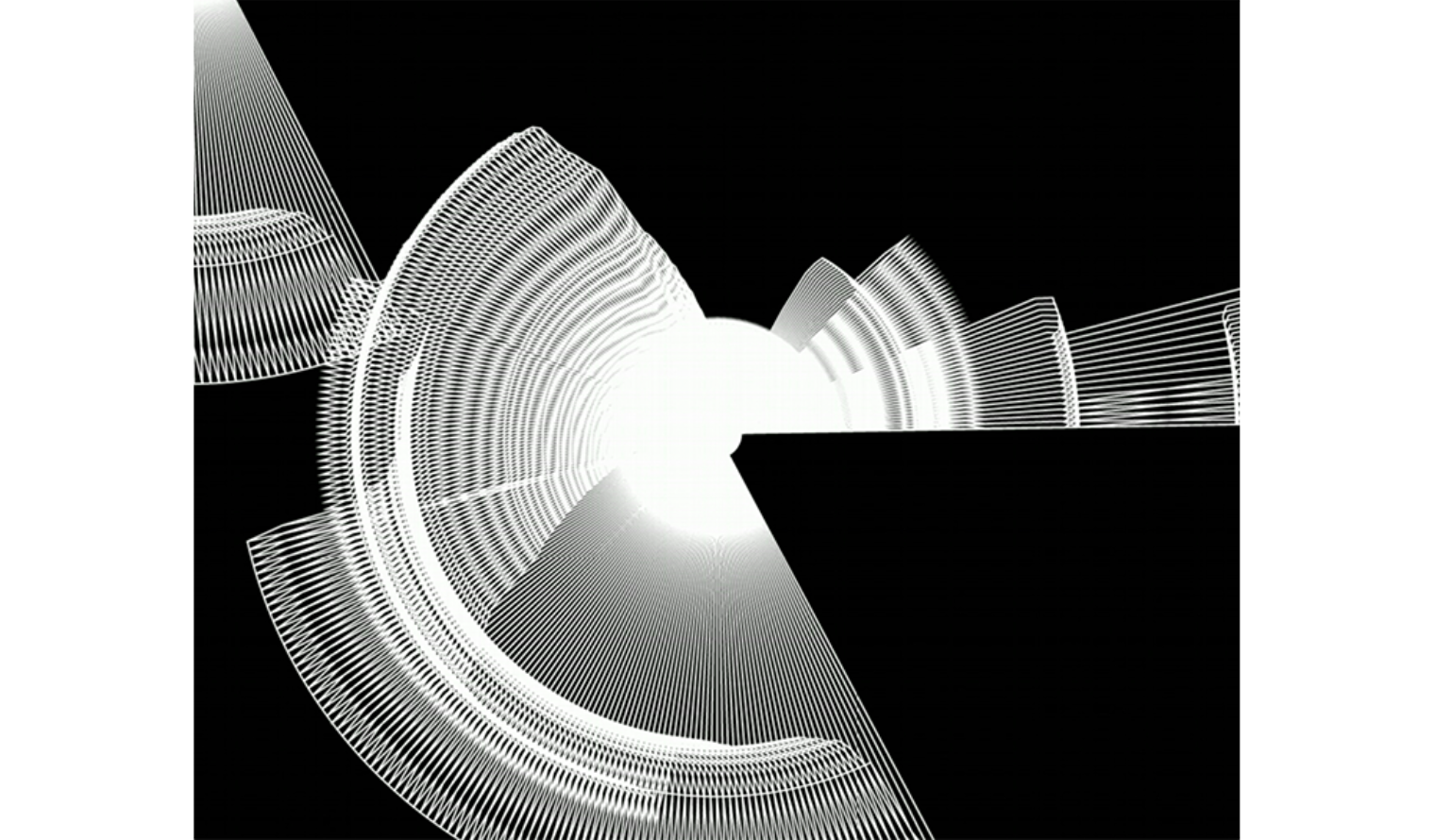

I believe it can. I am using data as an art material. My work for Woman in the Machine involves the translation of a natural system: I create a custom-designed algorithm that takes the recorded environmental data and uses it to generate audio and coded drawings. The work comes to life gradually as the received weather data changes.

In creating this algorithmic system, I am aware that I am making subjective decisions around the manipulation of data: about the frequency of data collection and other parameters of the software. In this way, the work reflects on ideas of objective knowledge, how algorithms work and how the decisions we make when transcoding data are not always impartial.

How do you use data to generate sound and image?

Using the programming language Processing, I custom design algorithms that respond to the recorded environmental data. I then use this to modulate the frequency of a sine wave oscillator, generating data-driven audio and coded drawings.

Some of the algorithms are more complex than others. With Processing, you can change other parameters of modulating sounds using ‘envelopes’, a set of coded instructions that can be configured to give you a pre-defined amplitude distribution over time. I manipulate the coded parameters of the envelopes’ amplitude distribution until I find a range that responds to the data and sounds interesting. I used them here to create that ‘click’ sound you often hear in electronic music.

In other works, I recorded the soundscapes generated by data and then used an analysis algorithm called Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to visualise the sound. FFT is used to isolate individual audio frequencies within the waveform and computes amplitude values along the frequency domain. Using these values I then create a data-driven radial drawing/animation.

I like to learn as much as possible about the technology I am working with and write the code if possible. This means when I am creating the final piece I know how changing a line of code changes the work and this gives me more creative freedom. I also love the process of creative coding, because if you accidentally come across something interesting while working through a problem you can follow that impulse or idea.

Do you tend to work on your own or in collaboration with others?

I find the most interesting methodology/approach to take in working with code and hardware technologies is learning by doing, working on projects and having a network of peers around you working in the same area. I have been lucky to collaborate on a number of projects with researchers from various fields, at the Sonic Arts Research Centre in Belfast, the Space Science group at UCD. As this area of research is quite underdeveloped in Ireland, I was lucky to take a course in interaction design at Malmo University Sweden and also to spend some time at Dark Matter Manufacturing, a studio run by a collective of artists, engineers, designers and scientists based on the top floor of a disused bank building in Brooklyn, New York. This interdisciplinary collective was started by a group of friends from MIT, it was a really inspiring place to be. The School for Poetic Computation was in the same building at the time. More recently, I have also been a satellite member of a group of artists and researchers at CONNECT, the Science Foundation Ireland Research Centre for Future Networks and Communications at Trinity College Dublin.

What are a couple of the pieces of technology you’ve used, and how do they work?

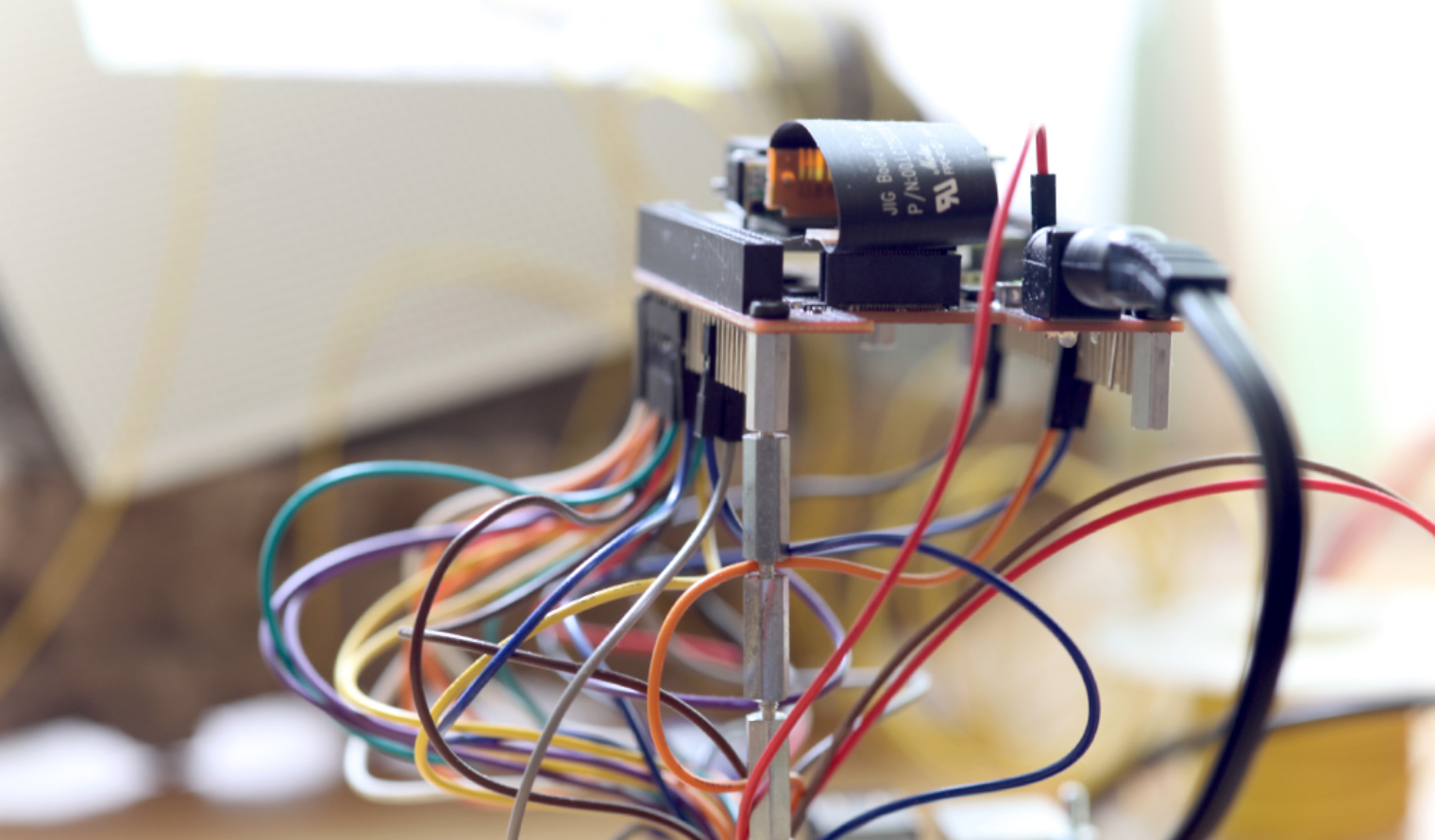

The Taoglas IoT sensor kit has very high precision positioning. It has three inbuilt sensors: ambient light, heat and humidity. Building the hardware for a robust sensor kit that can be mobile and battery-powered is not so easy, especially having a mobile kit that you can bring to hard to reach places in the mountains, gather data and send it directly in real-time to the cloud. I then use Processing, a programming language, to get this data from Taoglas API and relay a dynamic living landscape and fluid environmental conditions in digital form, translating the data into a generative drawing and data sonification.

The data-driven animations and sound compositions are running on four Raspberry Pis (single-board microcomputers) situated across the gallery. Though physically separate, the soundscapes overlap in the acoustic space. I was also excited to run the Texas Instrument Mini Projector as a display for one of the works. I was really pleased to see this tiny device working.

In my works, I often expose or leave transparent the material components. The inner workings are left exposed – Raspberry Pis, circuit boards, wires, electronic components, sensors – revealing the role of the machine. The work attempts to draw a parallel between the complex mechanisms in the natural world and the artificial.

Does electronic music have any influence on your work?

Yes, I certainly spent a lot of my 20s and 30s listening to electronic music with friends.

Because of this, I was drawn to artists working with electronic sound. I was always a huge fan of Carsten Nicolai’s work and the minimal electronic compositions he creates under the pseudonym Alva Noto. His work crosses between visual and sonic media, often manifesting the invisible forces that shape the physical world at both a macro and micro level: magnetic fields, radiation and sub-frequency sounds. As Alva Noto, he brings this experimentation into the field of electronic music.

How can technology help us get closer to nature?

Sensors can monitor the slow small changes and fluctuations which occur in nature over a long period of time. A data-driven artwork comes to life gradually as the data received changes. In this way the machine/artwork can act as a living organic system, reflecting nature and how it is constantly changing. When you are working with natural systems, using real-time data can add an extra layer of intrigue or surprise to an artwork. It brings the viewer into that moment in time and has the potential to bring the viewer closer to nature.

At the same time, I am aware that technologies and their infrastructures can often be human-centred. I am interested in questions around the idea of how technologies of the future can place other non-human ecosystems at the centre of their inquiry. Given the climate crisis, I am interested in exploring how digital objects and technologies (e.g. IoT) that are increasingly part of our everyday life can lead to new models and experiences for living ethically.

Can you tell us about a ‘woman in the machine’ who has informed or inspired your work?

It is interesting to reflect on the network of inspiring female scientists, engineers, artists, friends and peers who have been pioneering in establishing this field of inquiry both in Ireland and internationally. Recently I have been inspired by the work of the artist Tega Brain, an Australian-born, New York-based artist and environmental engineer, making eccentric engineering. Her work intersects art, ecology, and engineering and takes the form of dysfunctional devices, eccentric infrastructures and experimental information systems.

Artist Julie Freeman’s work has focused on using electronic technologies to ‘translate nature’ – whether it is through the sound of torrential rain dripping on a giant rhubarb leaf, a pair of mobile concrete speakers that lurk in galleries haranguing passersby with fractured sonic samples, or by providing an interactive platform from which to view the flap, twitch and prick of dogs’ ears. Her piece The Lake used hydrophones, custom software and advanced technology to track electronically tagged fish and translate their movement into an audio-visual experience.

A scientist who has inspired me is Astrophysicist Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell. In 1967 she discovered Pulsars – whirling stellar corpses that send beams of radio waves across the cosmos. With them, scientists can test some of the most fundamental theories in physics, detect gravitational waves, navigate the cosmic ocean, and maybe even communicate with aliens. Bell Burnell has spent her career working to uplift women and minorities in science.

Interview by Rosa Abbott

Woman In The Machine runs at VISUAL Carlow from 4 June – 12 September 2021. You can watch Fiona Mc Donald's digitally native work on womaninthemachine.com here.

RESOURCES

Useful links for budding coders!

- Adafruit – for sourcing electronic components and boards with tutorial support. Adafruit Industries was started by another inspiring woman in the machine: MIT graduate Limor Fried.

- Processing – a programming language for learning to code within the context of the visual arts.

- Raspberry Pi – makers of compact computers, used by artists working with technology, engineers, in robotics and sensor technology.

- StackOverflow – a forum used by web developers to ask questions or troubleshoot within the community. A valuable resource for coding beginners and learners!

- Glitch.com – an online community for discovering apps, bots and VR experiences.

- Github – a website for saving and sharing code in the cloud.

- Arduino – an open-source electronics platform based on easy-to-use hardware and software; intended for anyone making interactive projects.

![Install shot of Fiona Mc Donald, [Blanket bog ~ 7130] in Woman in the Machine. Photo credit Aisling McCoy](https://visualcarlow.ie/images/uploads/gallery/_1520x890_crop_center_90_none/Install-shot-of-Fiona-Mc-Donald-Blanket-bog-7130-in-Woman-in-the-Machine-Photo-credit-Aisling-McCoy.jpg)

![Still from Fiona Mc Donald [Blanket bog ~ 7130]](https://visualcarlow.ie/images/uploads/gallery/_1520x890_crop_center_90_none/Still-from-Fiona-Mc-Donald-Blanket-bog-7130.png)

![Still from Fiona Mc Donald, [Ambient Light ~ OSc]](https://visualcarlow.ie/images/uploads/gallery/_1520x890_crop_center_90_none/Still-from-Fiona-Mc-Donald-Ambient-Light-OSc.png)